The revenue service was initially established in the 13th Century when taxes were imposed on certain goods. Over the years, the service was extended as custom houses were built in ports where the Tax Collector and other officials operated and illegal contraband was stored. By the 18th Century, the government was losing substantial sums of money to smuggling gangs throughout the country. As such, a service was established to police the coast and catch smugglers at sea.

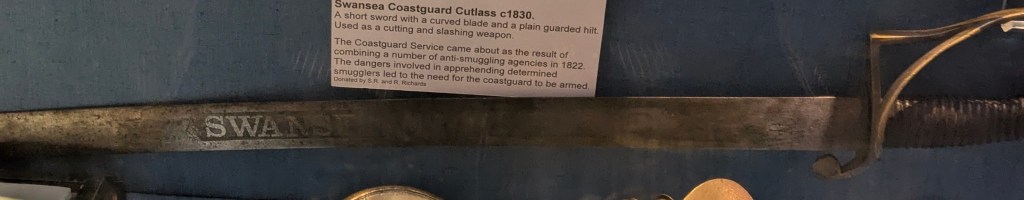

“They came on duty at dusk and went to bed at dawn. Every night they were assembled in the watchroom, armed with pistol and cutlass or with musket or bayonet … no man was given his instructions until he reported for duty and he was forbidden to communicate with his family after he received them … the guard was inspected twice a night to see if it was alert and watchful” – The routine duties of a revenue officer during the 18th Century.

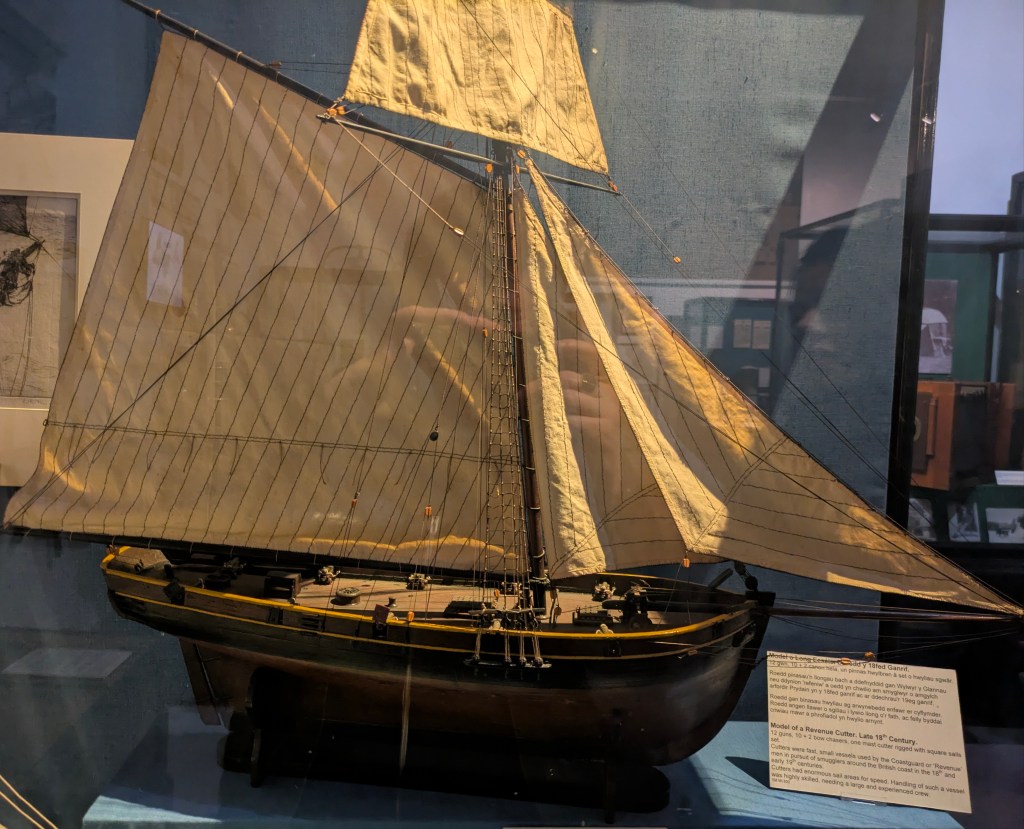

In 1800, the revenue service had 40 ships carrying a total of 200 cannons and crews comprising some 700 men. They were expected to sail the coasts, particularly at night and during bad weather, as these were the times that smugglers operated. Quite often, smugglers were able to bribe revenue officers who would happily turn a blind eye to illegal activities for financial compensation or a cask of brandy or tea.

Revenue officers received a modest wage for their services but this was supplemented with rewards for results, specifically, any untaxed goods they seized would be sold and the proceeds shared between the revenue officers and the ship’s owner, after the government had received its half share, known as the ‘King’s Share’. Most of the ships used by the revenue service were privately owned and hired by the Customs Board.

Traditionally, revenue officers wore red shirts and blue trousers, while the captains and the mate wore a long blue coat with brass buttons, the button holes being embroidered with silver thread and a cocked hat with a cockade. Each officer was armed with a cutlass and a pistol.

Alongside the revenue officers at seas, the service also had officers patrolling the coasts on horseback, the riding officers. These were established in 1698 and were stationed along the coast, up to ten miles apart depending of the terrain and the amount of smuggling in the area. The chief riding officer would be responsible for six officers who searched the coasts for smugglers on beaches or hidden in coves.

In 1745, an act was passed allowing the owner of any ship loitering within five miles of the coast or in a navigable estuary to be brought before a magistrate’s court, and if they could not explain their presence sufficiently, would be sentenced to a month’s hard labour. From 1746 onwards, anyone injuring or killing a revenue officer would be sentenced to death, and anybody found guilty had a choice between paying a fine, going to prison or being enlisted in the navy.

Local authorities could also be fined. A county could be fined £200 if illegal goods were found within its boundaries. If a revenue officer was attacked in the county, the local authorities would have to pay a fine of £40, and if an officer was killed, the fine was £100. However, if the smuggler responsible was caught within six months the fine would be revoked.

Of course, revenue officers had restrictions and rules about how to conduct themselves. If they seized a ship and were unable to find goods on board, the owner could claim compensation. To pursue a ship without being certain of its illegal intent would not help to further an officer’s career. Also, the revenue cutter could not stop a ship outside territorial waters without good cause. Otherwise, they could be accused of piracy, a defence often used by smugglers. Therefore, the revenue officers had to be sure of their exact location when seizing a ship.

“When a ship is seized, the officer should take special care to immediately note the depth as well as the distance from land to two points on the shore at the exact time the ship was seized and that in the presence of two or more officers …” – Instructions to revenue cutter captains issued in 1832.

Some coastlines were monitored better than others. Throughout the late 18th Century, the revenue service only employed three men to guard the extensive coast of Gower. This is likely the reason smuggling was commonplace during the period. Smuggling gangs often outnumbered the revenue officers. They would often have to request reinforcements from the government, but it could take weeks for the government to respond and send troops into the area. Smuggling gangs would often take advantage of these conditions. If they were tipped off about the revenue officers’ intentions, the smugglers could remove and hide their contraband in another location. For example, William Hawkins Arthur and John Griffiths would often get informed about the revenue service calling on the government for reinforcements and prepared for their arrival.

As the illegal trade grew, the more people took part in it. On occasion there were gangs of several hundred men involved in some local authorities. Sometimes, smugglers were confident enough to land the goods in broad daylight, and they would often attack revenue cutters. As such, the work of the revenue officer was extremely dangerous. In a report published by the revenue service in 1736, it was said that 250 revenue men had been attacked or injured since Christmas 1723, and that six had been killed.

Further Reading

- W. J. Ashworth, Customs and Excise: Trade, Production, and Consumption in England, 1640-1845, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

- E. K. Chatterton, King’s Cutters and Smugglers 1700-1855, (London: George Allen & Co., Ltd., 1912).

- T. Elias and Dafydd Meirion, Smugglers of Wales, (Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 2017).

- K. Watkins, Welsh Smugglers, (Cornwall: James Pike Ltd, 1975).

- P. Ferris, Gower in History: Myth, People, Landscape, (Hay on Wye: Armanaleg Books, 2009).

- J. G. Jenkins, Welsh ships and sailing men, trans. Martin Davis, (Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 2006).

- W. H. Jones, History of the Port of Swansea, (Carmarthen: W. Spurrell & Son, 1922).

- J. Richards, Maritime Wales (Stroud: Tempus Publishing Limited, 2007).

- C. Smith, Mumbles Lifeboat: The Story of the Mumbles Lifeboat Station since 1832 (Swansea: Sou’wester Books, 1989)

- D. Hay, “Property, Authority and the Criminal Law,” In Albion’s Fatal Tree, (New York: Pantheon, 1975) pp.17–64.

- D. C. Smith, ‘Fair Trade and the Political Economy of Brandy Smuggling in Early Eighteenth-Century Britain’, Past & Present, 251.1 (2021), pp.75–111

Leave a comment