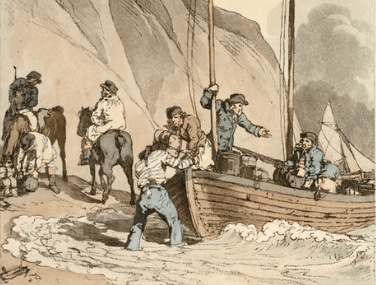

What is Smuggling? Smuggling in its simplest form is the illicit movement of goods into or out of a country. It was one of the most organised and widespread criminal activities in Wales and the rest of the British Isles during the 18th Century. Often many people engaged in the activity from various locations, moving a variety of goods throughout England and Wales. Smugglers (or smyglwyr in Welsh) were often creative in the ways they carried illicit goods as different types of goods needed specific methods of transport and various regions developed their own smuggling customs based on geographical location and cultural conditions.

Smugglers situated in the west and north of the country would easily manipulate import and export regulations by moving goods from Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. While those in the southern and eastern regions engaged in illicit trade with merchants in Holland and France. While the types of goods varied, Welsh smugglers favoured tobacco, tea and alcohol, particularly gin and brandy. They also moved luxury items such as lace, silk, and linen. Smugglers tended to be members of working class such as mariners and labourers who supplemented their exploitative wages with the proceeds from illicit free trade.

For example, the infamous William Hawkin Arthur from Pennard in Gower was the leader of a large gang of smugglers that operated in the Bristol Channel. He lived in Great Highway Farm which he used to store and hide illegal contraband. One of Arthur’s ships called The Cornwall, was constantly stationed at Devon. It was a pilot boar of about 20 tons which was used to meet larger ships which had reached the Bristol Channel and take illicit goods from them before heading into port.

The Cornwall had been caught several times with illegal contraband onboard, but every time the captain had a sufficient excuse and was released. This changed in 1783, when The Cornwall was caught with a large amount of gin and tea on board. The ship and goods were seized by the revenue men. Arthur subsequently wrote to the revenue service asking them to release his ship as the tea and gin had been placed on board without the knowledge of the captain or himself. The revenue service refused Arthur’s request and The Cornwall was sawn into three sections and sold to pay costs and provide a reward for the revenue men.

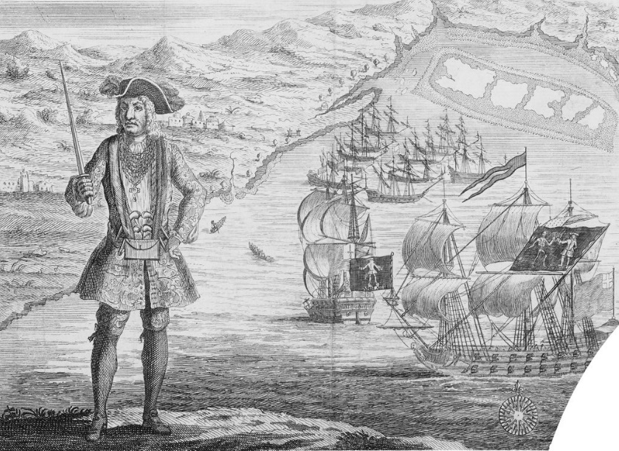

What is piracy? The legal definition of piracy is “to seize goods illegally at sea.” Some sources claim that Wales has produced more pirates per mile of coastline than any other country in Europe. Many pirates during the 17th and 18th centuries were of Welsh decent. The infamous Captain Henry Morgan and Bartholomew ‘Black Bart’ Roberts were amongst the foremost pirates to sail the seas during the Golden Age of Piracy.

The Welsh word for pirate is môr-leidr which means sea-thief but there are several other terms such as privateer and buccaneer that are often associated with piracy. At times, it is difficult to differentiate these terms, but they do have some distinctions. A privateer (or preifatwr in Welsh) was somebody who attacked an enemy country’s ships with the approval of their state. For much of British history, the English Monarchy and Parliament would grant certain individuals with immunity from prosecution if they attacked enemy ships, usually the Spanish. Privateers were given letters of marque from the Crown which gave them written permission to attack enemy ships. Quite often, someone would start out as a privateer during wartime but as the English Crown’s allegiances changed or when peace was declared, the privateers would find themselves classed as pirates.

This happened to the infamous Captain Henry Morgan had enjoyed the support of the Crown to attack Spanish ships in the Caribbean, but as he and his men ventured across the Panama isthmus to attack Panama City, England and Spain began peace negotiations. As a result, Henry Morgan was summoned to London where he was charged with piracy to appease the Spanish ambassador.

What about buccaneers? This is a term that was used primarily in the Caribbean during the Golden Age of Piracy, and as such has no Welsh equivalent. By 1640, the island Hispaniola was a haven for pirates operating in the Caribbean. Wild pigs and cattle roamed the island since they had been left there by Spanish settlers who realised quickly that the island was insufficient to raise cattle. Many of the inhabitants of Hispaniola turned to piracy so they could make a living by plundering Spanish ships who were passing through the Caribbean bringing gold, silver and other goods from the New World. Once ex-soldiers settled the land in Hispaniola, they started to hunt the animals that had been left to run wild on the island. The natives’ method of preserving meat was to dry it slowly over the fire, to produce boucan, and this was picked up by the ex-soldiers who slowly became known as buccaneers. As the buccaneers followed the other natives into piracy, the term became associated with anybody committing sea-based crimes in the Caribbean.

Before the 17th Century, there was only one name for sea plunderers and that was ‘pirate’ or ‘pyrate’. One of the earliest references to pirates in Welsh history comes from one of the heroic poems Brut y Tywysogion, which mentions that Rhys ap Tewdwr received the help of Irish and Scottish pirates to reclaim Deheubarth in South Wales:

… y rodes rys ap Tewdwr swllt yr herwlo[n]gwyr

y sgottyeid or gwyddyl adathoed yn borth ydaw …

The word ‘pirate’ comes from the Latin word pirata, which derives from the Greek word peirates, from peirein, meaning to attack. There were many reasons why people resorted to piracy. Particularly, economic conditions during the Age of Sail (1400s-1900s) determined an individuals’ aspirations of piracy. The poor conditions aboard English merchant ships and the Royal Navy motivated many people into a life of piracy or smuggling to make ends meet or carve out a better life for themselves and their families.

This was the case for John Callis, a 16th Century pirate who operated in South Wales, between Cardiff and Haverfordwest and became known as “the most dangerous pyrate in the realm”. Callis first sailed as an officer in the Royal Navy under Sir John Berkeley but soon turned to a piratical career that lasted decades. Eventually, he was captured in 1576 after mounting pressure from neighbouring nations forced the English government to take action. He was hanged in Newport later that year. During his time as a pirate, he would often smuggle his prizes into the villages of Laugharne and Carew in Milford Haven, only a few miles south of Little Newcastle, where he would sell his illegal contraband.

John Callis is an example of someone who was both a pirate and a smuggler. While there are clear differences between a pirate and a smuggler, the terms are not mutually exclusive. Very often, pirates would have to smuggle their plundered prizes onto land so they could sell it and make a profit, while a few smugglers acquired their illegal contraband by seizing it illegally at sea. Of course, only a minority of people involved in smuggling resorted to piracy, but there are enough examples of individuals doing both for these terms to be interrelated. For instance, John Lucas of Port Eynon was infamously both a smuggler and at times a pirate. He was given the Salt House in Port Eynon by his father and proceeded to fortify it and use it as a base of operations for his illegal activities. He also repaired the nearby Culver’s Hole making it “ … both inaccessible save for a passage thereunto through the clift …” It was said that Lucas “secured ye pirates and ye French smugglers and rifled ye wrecked ships and forced mariners to serve him”.

Further Reading

- Platt, Smuggling in the British Isles : A History (Stroud: The History Press, 2011).

- Watkins, Welsh Smugglers, (Cardiff: Viewing Wales Series, 1975).

- Elias & Meirion, Smugglers of Wales (Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 2017).

- Meirion, Welsh Pirates (Talybont: Y Lolfa, 2006).

- Breverton, The Book of Welsh Pirates and Buccaneers (Sain Tathan, Bro Morgannwg: Wales Books, Glyndŵr Publishing, 2003).

- Thomas, The Buccaneer King: The Story of Captain Henry Morgan, (South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Maritime, 2014).

- Breverton, Terry, Black Bart Roberts : ‘The Greatest Pirate of Them All’ (St. Athan: Glyndŵr Publishing, 2004).

- Statham, Privateers and Privateering (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- Reasons Humbly Offered against Some Clauses in the Present Bill for Encouragement of Privateers (London: s.n., 1695).

- Stockton, Frank Richard, Buccaneers and Pirates of Our Coasts (Project Gutenberg, 2005).

- Caradoc & University of Wales, Board of Celtic Studies, Brut y Tywysogyon, Peniarth MS. 20 (Caerdydd [Cardiff: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru, 1941).

- Taylor, Sons of the Waves : The Common Seaman in the Heroic Age of Sail (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020).

- Hawkes, “Illicit trading in Wales in the eighteenth century,” Maritime Wales, 10 (1986): pp.89-107.

- Ferris, Gower in history: myth, people, landscape (Hay on Wye: Armanaleg Books, 2009).

Leave a comment